Wounds That Never Heal: Remembering Operation Bluestar

OPERATION BLUE STAR

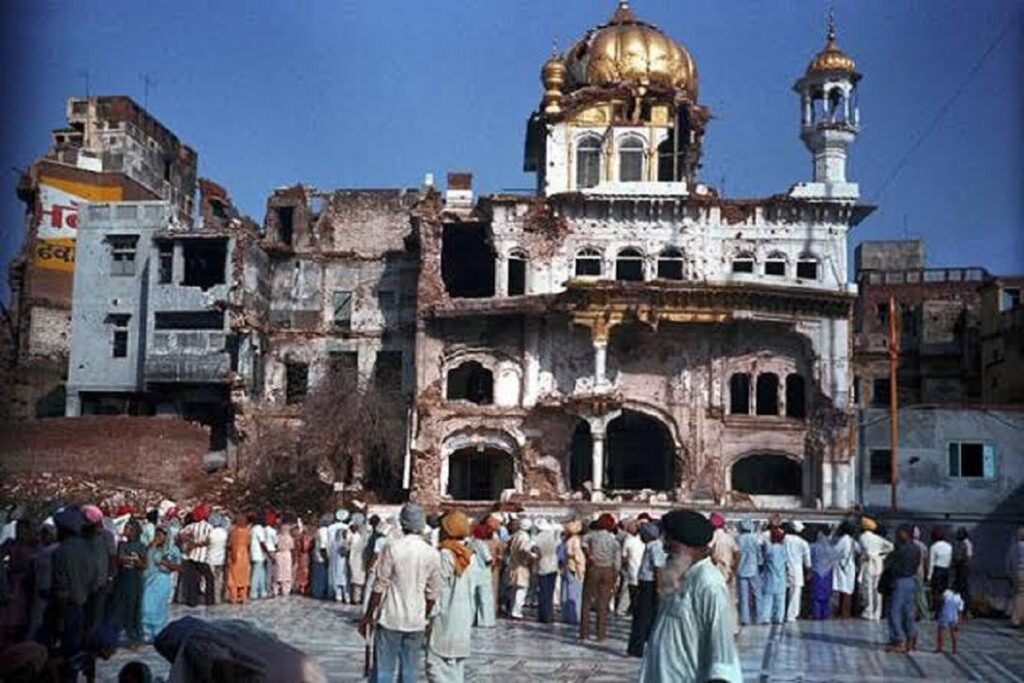

The military action at the Golden Temple in 1984 has left a lasting impact on generations of Sikhs, leaving many to try and piece together fragments of painful pasts.

It happened 37 years ago but it feels as if it was yesterday – the heart, body and mind still feel the tremors of the emotional earthquake it caused. The force of those tremors intensifies every year when June 6 approaches. Operation Bluestar (saka neela tara), a fancy-sounding name given to a dreadful military action at the Sikhs’ holiest shrine, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, was launched on June 2, 1984, with a ‘national broadcast to the nation’ by then prime minister Indira Gandhi. It was claimed to have been completed successfully on June 6 with the ending of the last resistance by Sikh combatants to the army’s entry at the Temple. State media (TV and radio) and other non-state media outlets praised the operation for saving India’s ‘unity and integrity’ from ‘anti-national’ Sikh secessionism.

The most reliable estimates of the total number of deaths during Operation Bluestar range from 5,000 to 7,000. It was a tragedy that could have been avoided if – and it is a big if – Indira Gandhi had had the vision to reach a political settlement with the moderate Akali leadership. Most Akali Dal demands – regarding federal decentralisation, river water rights, territorial readjustment and the transfer of Chandigarh to Punjab as its capital – could have been negotiated. Rajiv Gandhi did agree to each of these demands, and many more besides, in the 1985 Rajiv-Longowal Accord. He implemented none.Indira Gandhi’s political decision to use the ‘Hindu card’ to gain electoral victories led her to choose a dangerous path of confrontation, first with the Akalis and eventually with the entire Sikh community. This miscalculation cost Mrs Gandhi her life, and left the communities of Punjab and of India in general scarred and polarised. This polarisation peaked with the genocidal violence against the Sikh minority in Delhi and many other North Indian Hindu majority towns in November 1984 after the assassination of Indira Gandhi by two of her Sikh security guards. Sikh nationalists in Punjab were eventually defeated, at least militarily, by the 1990s, but Hindu nationalism was promoted so powerfully that the Hindu nationalists succeeded within a few decades in capturing the Indian state.

In the Sikhs’ collective memory of 1984, the deaths by army action in June and those by genocidal mob violence in November constitute two ends of the same arc of killings. The two cannot be separated and, therefore, remain indelibly linked to the memory of Operation Bluestar, which is seen as the trigger both for the killings and for later disappearances, killings in custody and deaths by ‘encounters’ during the military operations against the armed Sikh opposition movement after the events of 1984.

Operation Bluestar is gradually finding a place in the Sikh practice of ardaas (prayer). This practice is unique in the history of world religions because it gives collective memory a central place. On all important occasions – birth, marriage, death, new job, promotion, passing an examination, new house, Gurpurab celebrations (in honour of the gurus’ birthdays), or even the daily rituals in a gurdwara – the ardaas recounts in capsule form the history of the Sikh faith.

The most reliable estimates of the total number of deaths during Operation Bluestar range from 5,000 to 7,000. It was a tragedy that could have been avoided if – and it is a big if – Indira Gandhi had had the vision to reach a political settlement with the moderate Akali leadership. Most Akali Dal demands – regarding federal decentralisation, river water rights, territorial readjustment and the transfer of Chandigarh to Punjab as its capital – could have been negotiated. Rajiv Gandhi did agree to each of these demands, and many more besides, in the 1985 Rajiv-Longowal Accord. He implemented none.Indira Gandhi’s political decision to use the ‘Hindu card’ to gain electoral victories led her to choose a dangerous path of confrontation, first with the Akalis and eventually with the entire Sikh community. This miscalculation cost Mrs Gandhi her life, and left the communities of Punjab and of India in general scarred and polarised. This polarisation peaked with the genocidal violence against the Sikh minority in Delhi and many other North Indian Hindu majority towns in November 1984 after the assassination of Indira Gandhi by two of her Sikh security guards. Sikh nationalists in Punjab were eventually defeated, at least militarily, by the 1990s, but Hindu nationalism was promoted so powerfully that the Hindu nationalists succeeded within a few decades in capturing the Indian state.

In the Sikhs’ collective memory of 1984, the deaths by army action in June and those by genocidal mob violence in November constitute two ends of the same arc of killings. The two cannot be separated and, therefore, remain indelibly linked to the memory of Operation Bluestar, which is seen as the trigger both for the killings and for later disappearances, killings in custody and deaths by ‘encounters’ during the military operations against the armed Sikh opposition movement after the events of 1984.

Operation Bluestar is gradually finding a place in the Sikh practice of ardaas (prayer). This practice is unique in the history of world religions because it gives collective memory a central place. On all important occasions – birth, marriage, death, new job, promotion, passing an examination, new house, Gurpurab celebrations (in honour of the gurus’ birthdays), or even the daily rituals in a gurdwara – the ardaas recounts in capsule form the history of the Sikh faith.

The ardaas narrative starts with the founding of the faith by Guru Nanak, its continuation by his nine successors and the sacrifices made by the tenth guru Guru Gobind Singh’s four sons (sahibzade), the five Beloved Ones (panj piare), the 40 Liberated Ones (chali mukte) and numerous other martyrs right up to the present time. Sikhs have a long memory. Udham Singh waited for 21 years to avenge the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 by assassinating Michael O’Dwyer in 1940. The Naxalite Sikhs punished a Sikh landlord Ajaib Singh Kokri, a witness against the revolutionary Bhagat Singh, by assassinating him in 1974, 43 years after Bhagat Singh was hanged in 1931. The socialisation from early childhood of anyone growing up in a Sikh household (irrespective of the political affiliation of the household) involves such a focused exercise in historical remembrance that most adult Sikhs remember the ardaas by heart, whether they are illiterate farmers or university academics. The ardaas contributes to the making of an active historical being who remembers the past, relates that past to the present and imagines the shaping of the future.

Operation Bluestar has come to be remembered as the teeja Ghallughara (the third holocaust). Many gurdwaras outside India and perhaps some even in India have incorporated the remembrance of the teeja Ghallughara in the ardaas. In Sikh historical memory, there have been two Ghallugharas before Operation Bluestar – the chhota Ghallughara (the small holocaust) and the wadda Ghallughara (the big holocaust). The chhota Ghallughara took place in May 1746 when, according to estimates made by the celebrated Sikh historian Professor Ganda Singh, about 10,000 Sikh men and women were killed. The wadda Ghallughara took place in February 1762 when about 30,000 Sikh men, women and children were slaughtered. According to one as yet unconfirmed estimate, about half of the total Sikh population was liquidated during the wadda Ghallughara.

These were the darkest times in the history of the Sikhs. These massacres could have demoralised them to the point of extinction, but, inspired by the memories of their gurus and martyrs, they regrouped and within a few decades of the wadda Ghallughara, emerged literally from the ashes to become the de facto rulers of Punjab in the last quarter of the 18th century. By 1799, one of them (Ranjit Singh) formalised that de facto rule to become the Maharaja of Punjab. The force of memory weighed upon him too and he ruled, therefore, in the name of the gurus. Some features of feudal degeneration which emerged during his rule were the result of his dissociation from the memory of the path of the gurus.

During the dark times the Sikh community faced from 1716, when the Sikh warrior Banda Singh Bahadur was martyred, to 1799 when Ranjit Singh came to power, Harmandar Sahib (later known more popularly as the Golden Temple) became the nerve centre for the moral, political, military, spiritual and even economic empowerment of the community. While living the life of guerrilla combatants against the Moghul powers, the leading members of the community would meet twice a year on Vaisakhi and Diwali for deliberations and collective decision-making for the future survival of the community. Once in the precincts of the Harmandar Sahib, they considered themselves protected by the Guru and had no fear of any earthly powers such as the Moghul rulers they had to confront. The mystique of the Harmandar grew and this mystique has continued and strengthened over the centuries. The Golden Temple has literally become the heart of the community.

The death, destruction and sacrilege caused during Operation Bluestar pierced the heart not only of the Sikhs but also of many Punjabi Hindus. The devastation it caused in the personal lives of so many millions has still not been fully recorded and acknowledged because the political divide over the attitudes towards Operation Bluestar has overshadowed the human stories.

The wounds may never heal but by connecting your pain to the pain of others, the meaning and experience of pain is transformed.